A Library is a magical place: all those books jammed together, whispering and daring each other to grab the attention of unsuspecting patrons and teach them a thing or three. I am certain I was the subject of just such a conspiracy. I had chosen my stack of books and was ambling contentedly toward the checkout machines when I made an unplanned right hand turn toward the mystery section. Maybe just one more, I thought. A mystery. Haven’t read a good murder mystery in awhile. My eyes skimmed the titles and immediately lit on an ornate font that hinted at a medieval murder mystery, my favorite. I plucked the book from the shelves and sure enough, it was The Song of the Nightingale, one of the Hawkenlye Mysteries by Alys Clare, set in early 13th century southern England. In retrospect, I’m sure I heard a triumphant “Gotcha!” as I added the book to my stack.

A Library is a magical place: all those books jammed together, whispering and daring each other to grab the attention of unsuspecting patrons and teach them a thing or three. I am certain I was the subject of just such a conspiracy. I had chosen my stack of books and was ambling contentedly toward the checkout machines when I made an unplanned right hand turn toward the mystery section. Maybe just one more, I thought. A mystery. Haven’t read a good murder mystery in awhile. My eyes skimmed the titles and immediately lit on an ornate font that hinted at a medieval murder mystery, my favorite. I plucked the book from the shelves and sure enough, it was The Song of the Nightingale, one of the Hawkenlye Mysteries by Alys Clare, set in early 13th century southern England. In retrospect, I’m sure I heard a triumphant “Gotcha!” as I added the book to my stack.

I enjoyed the book mostly because of its view into the trials of England under the reign of King John. As its Kirkus Review https://www.kirkusreviews.com/book-reviews/alys-clare/song-nightingale/ states, it’s “much stronger on history than mystery.”

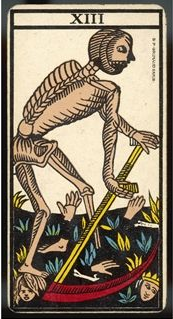

And history was the reason the book decided it needed to come home with me. The main character’s son had become involved with the mysterious Cathars of the Languedoc. They ask him to take the book of their teachings, the story of the hero’s journey or Pilgrim’s Progress told in pictures, into England to keep it safe. As it turns out, this “book” is the first Tarot deck.

Great premise.

It caught my attention.

Was it possible that the Tarot was created by this doomed sect of heretics in southern France?

Christ and the four archangels

An afternoon of research on the internet convinced me that this was not the case. It looked really good at first. The Cathars, or, as they called themselves, Bons Hommes:

- were dualists. As we saw in The Sun key, the Tarot is full of yin-yang symbolism and also angels and devils. The Cathars were big on The Devil, who created the material world and tainted it with his vileness, tempting us away from the spiritual world, the kingdom of God.

- stressed, like most of the heretical sects of the time, a personal journey toward enlightenment, unhampered by the dogma of the Catholic Church. The Tarot is a guide to just this sort of journey.

However, the timing is not quite right. The Cathars did manage to hang on in northern Italy into the mid 1300’s, and although the Visconti-Sforza tarot, the oldest known deck, was also created in northern Italy, it didn’t appear untill the mid 1400’s a full century after Catharism had been crushed.

But the kicker, as far as I’m concerned is that the Cathars mistrusted the material world because it was the filthy creation of Satan. No statues, paintings, or any other attempt to capture spirituality in a material form, graced their meeting places.* Why would they choose to portray their sacred mysteries in the very paintings they abhorred?

But I had become fond of the Bons Hommes, even though they were totally anal retentive about many of the things I consider sacred—like sex, food, and art.

They did, however:

- encourage their devotees to think for themselves and follow their own inspiration.

- give women equal status to men because they believed that we are all asexual beings (read angels) trapped in a gender specific body.

- hate war.

- adopt a simple, ascetic lifestyle.

- believe in reincarnation.

In this day and age many of us would consider them to be “good human beings” indeed. I would like to think that they had some input into the tarot.

So I searched a bit further and found a treasure. “Catharism and the Tarot” by Robert V. O’Neill is a meticulously referenced treatise that follows the influence of the Cathars through history to a fascinating endpoint. He also concluded that the Cathars probably weren’t the sole originators of the tarot, but he shows quite convincingly that they did have an influence.

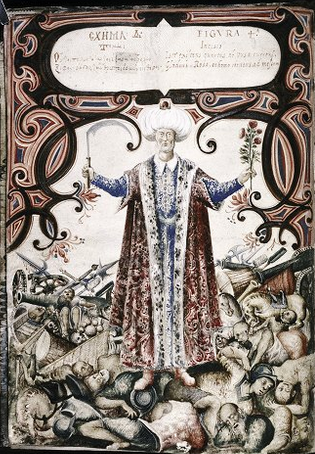

“Oracles of Leo the Wise”, Ashmole manuscript 1597, The Bodleian Library

The thing we tend to forget about history is that it isn’t as simple and straightforward as our textbooks would have us believe. Even in a time when horseback was the quickest way to get from point A to point B and the fate of a letter was iffy, everything still influenced everything else and one idea still led to five other ideas. It just happened much…more….slowly. O’Neill observes that just as the precepts of Catharism derived from earlier philosophies, those same ideas indirectly influenced the apocalyptic vision of Joachim of Fiore (c. 1130/35-1201/2 CE) which in turn influenced St. Francis of Assisi and the Franciscan order he started in the early 13th century.

To make a very long story short and less precise:

Joachim of Fiore was a priest in good standing of the Catholic Church who believed in the literal truth of the Book of Revelations. He prophesied that there were three ages of man. The third age of man would begin, of course, very soon with the coming of the antichrist. But the Antichrist would be overcome and Christ would rule once more due to the efforts of a few “spiritual men”. The Christ vs. Antichrist scenario is, of course straight out of Cathar dualistic theology. Other apocalyptic literature scenarios had also been put forth. One was collection of manuscripts known as The Oracles of Leo the Wise, only a few of which can actually be attributed to the Byzantine emperor Leo VI, (866–912 CE). The coming of the apocalypse was pretty heady stuff and Medieval Europe was abuzz with it for centuries.

Then came the Franciscan Friars, with their vows of poverty and close contact with the people. This is the same modus operendi that made the Cathars, whose priests, or perfecti, lived lives of poverty and taught among the common people, so popular. The Franciscans also gave equal status to women and encouraged individual spirituality. St. Francis even created a third branch of their order called the tertiaries, which consisted of lay people interested in developing spiritually—very much like the credentes, the lay portion of the Cathar faith.*

At this point, there was very little similarity between the Franciscans and Joachimism. However, with the death of St. Francis, the order splintered. The Spiritual Franciscans adopted Joachimism’s apocalyptic views and saw themselves as the few “spiritual men” and the Pope as the antichrist. A synthesis of conventional Franciscan ideas and Joachimism that was like Catharism—only different.

Now the Catholic Church came to realize that burning heretics was perhaps not the best strategy, especially when the heretic wasn’t directly condemning the Catholic Church, but was simply searching for his or her own spirituality. So it developed a sensible “if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em” approach. By the middle of the 15th century (right when the first tarot decks came out) the Church had transformed the popular laic Franciscan Tertiaries into Confraternities. These were squeaky clean and totally legal “independent religious fraternities (Terpstra,1995). They administered community charity (Pullen, 1971), commissioned art (Schiferl,1991), organized processions and religious dramas on Holy Days (Wisch and Ahl, 2000), and cared for abandoned children (Terpstra, 2000a). But beyond the charitable and ritual activities, they also supported a contemplative, individualistic spirituality for their members (Henderson, 1990).”* These institutions were very popular in northern Italy and their power and influence is well documented. By the year 1400 Florence had 52 confraternities. They were nexus points where the intelligensia, aritsans, and tradesmen met on equal footing and exchanged ideas with no intervention from the Catholic Church. Some even exist to this day. A confraternity runs Florence’s ambulance service.*

It was the Confraternities of northern Italy, according to O’Neill, that produced the first tarot decks. Everything was in place. The brains, the artists, and the know-how. They borrowed heavily from the Apocalyptic art (see the examples in this post) that had already captured the imagination of Europe.*

And so, if we believe Robert O’Neill, the tarot wasn’t invented by Gypsies, or some secret mystical sect, or even the Egyptians. It wasn’t a direct product of Jewish mysticism either. It was developed by progressive Catholics who used the existing Christian Apocalyptic art. And it was made possible by the most brilliant institution the Catholic Church ever developed—the Confraternity.

And I never would have discovered any of this if I hadn’t heard The Song of the Nightingale in the library.

*Catharism and The Tarot”, by Robert V. O’Neill

9 thoughts on “At Last! A Plausible Explanation for the Origin of the Tarot”

Fascinating stuff! Consider writing a book about your search for Tarot origins, and thanks for the author/book recommendation.

This is an interesting chronology. What I like best is how one piece, led to the next, to the next. . . It’s like that old synchronicity thing we were discussing awhile back! Thanks for the research, Chrissy! Those nightingale songs – many a songwriter has waxed poetic about their magic.

Thank you Chrissy! I loved this! I am astonished by the seeming ‘coincidences’ that lead to these revelations,

as I am astonished by so many things. What a grand mystery it all is, waiting to be deciphered!

Hi Silver,

Yes, life is indeed a grand mystery full of surprises and amazing twists.

Hugs to you.

Yes, that makes perfect sense. As I told you, the priests were using art to spread their messages and teach their flocks at the timeTarot appeared. When I visited Paris I was introduced to this idea. The priests had art on the walls of the cathedrals so they could tell Biblical stories and have an illustration to make their points/interpretations.

In a world where very few people could read, it was valuable teaching tool.

Interesting. I will contemplate it and love that I’ve come across this information while reading The Origins of the Tarot by Dai Leon. Thank you.

You are welcome.

Tracking down the Tarot is a fascinating task.