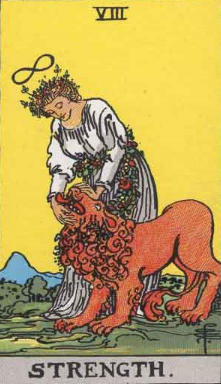

Whenever I read a story about werewolves, the lion on the Strength card roars in my head like the start of an old MGM movie. A tale about werewolves is always about the eternal struggle between our animal desires, instincts, and power and our logical, self-controlled, altruistic human side. At the end of the 2010 remake of the 1941 movie, The Wolf Man, the Wolf Man attacks his fiancée, forcing her to shoot him with a silver bullet. Her words, which end the movie, states the moral dilemma posed by Strength and the werewolf beautifully.

werewolves is always about the eternal struggle between our animal desires, instincts, and power and our logical, self-controlled, altruistic human side. At the end of the 2010 remake of the 1941 movie, The Wolf Man, the Wolf Man attacks his fiancée, forcing her to shoot him with a silver bullet. Her words, which end the movie, states the moral dilemma posed by Strength and the werewolf beautifully.

Only in killing a man

But where does one begin and the other end?”

In his latest book, The Last Werewolf, Glen Duncan’s line between man and beast is fairly clear and painfully raw. Jake is a werewolf from hell. A week before full moon the wulf, as he calls, it begins to mess with him. Phantom fangs and claws ripple out of his flesh and the urge to literally bite someone’s head off goads him constantly. At moonrise on full moon, he falls to the ground and writhes in agony as his joints pop and snap into new positions and he morphs into a fiend, part man, part wolf, with no mercy and an intense hunger that can only be satisfied by human flesh, especially the flesh of his loved ones. His every move is dogged by WOCOP (world organization for the control of occult phenomena) and vampires, who have discovered that something in a werewolf’s blood will make them light tolerant.

The were-animals in Charlaine Harris’s Sookie Stackhouse series (inspiration for HBO’s True Blood movies) are at the other end of the werewolf spectrum. They have it much easier. When they morph, it’s uncomfortable, but they get used to it, and are able to change into their animal whenever they want. And those animals aren’t hybrid monsters, they are beautiful wolves, tigers, etc. with human intelligence, blood lust, and short tempers. They usually stick to animals as prey unless some hapless human has aroused their ire. This means that they can still lead fairly normal lives. Harris’s separation of man and beast is a comfortable continuum.

Where a writer places his werewolf on this spectrum depends on what he’s trying to say and where he wants to go with his character.

Jake and The Wolf Man have only a slight amount of control over their beast. Their creators are writing heart-stopping, brutal horror. They force their audience to struggle along with the monster as he tries valiantly but in vain to control the beast, and to gasp in wicked wonder when he gives in and revels in the pure joy of running through the woods under a full moon and sinking his fangs into the throat of his terrified prey. We have sympathy for him because we know how demanding our own beast can be. In the 1941 version, the dying Wolf Man fades into his human self and says to his killer, “Thanks for the bullet, it was the only way.”

Jake and The Wolf Man have only a slight amount of control over their beast. Their creators are writing heart-stopping, brutal horror. They force their audience to struggle along with the monster as he tries valiantly but in vain to control the beast, and to gasp in wicked wonder when he gives in and revels in the pure joy of running through the woods under a full moon and sinking his fangs into the throat of his terrified prey. We have sympathy for him because we know how demanding our own beast can be. In the 1941 version, the dying Wolf Man fades into his human self and says to his killer, “Thanks for the bullet, it was the only way.”

But Harris gives her were-folk an option. They can control their beast. It’s difficult, but possible, and their struggles are the perfect metaphor for the Strength card. The good guys are in control of their beast and use it to help. Perfect heroes. The bad guys and also in control of their beasts, but they use them to harm. Perfect villains. And the weak struggle constantly to gain control over their beasts, give up, or just don’t care. The plight of the rest of humanity. Things always get interesting when the hero slips and uses his beast to harm or the villain slips and uses his beast to help. And the guilt and angst that happen when a character tries to control his beast but fails is much greater if he knows that he should be able to.

But Harris gives her were-folk an option. They can control their beast. It’s difficult, but possible, and their struggles are the perfect metaphor for the Strength card. The good guys are in control of their beast and use it to help. Perfect heroes. The bad guys and also in control of their beasts, but they use them to harm. Perfect villains. And the weak struggle constantly to gain control over their beasts, give up, or just don’t care. The plight of the rest of humanity. Things always get interesting when the hero slips and uses his beast to harm or the villain slips and uses his beast to help. And the guilt and angst that happen when a character tries to control his beast but fails is much greater if he knows that he should be able to.

I’ve been studying werewolves because I’ve added one to my second book. It’s an occult murder mystery and I needed a character with the skills of a werewolf to help Molly find “who done it” and survive. My werewolf will probably be more like Sookie’s friends than Jake.

And, OK, I couldn’t resist. I wanted to write about a werewolf.

4 thoughts on “Strength and the Werewolf”

We saw the more human side of the werewolf in the Harry Potter films where Prof Lupin (nice name) was a nice guy except when he got mixed up with moonlight in his eye. I wonder how many people saw the symbolism, as you describe it here, in those scenes.

Malcolm

The nice thing about symbolism in fiction is that the reader doesn’t even need to recognize that it’s there for it to be effective.

Our brains seem to be hard wired to pick up on symbolic and archetypal meanings at a subconscious level.

Yes, that’s such a plus, isn’t it. I once saw that described as similar to the process of striking one tuning fork and having a nearby fork begin to vibrate as well. Same thing seems to happen between symbols and our subconscious while we read or looking at paintings or films.

Malcolm

That’s a great analogy.