A few months ago Clio, my six-year-old grandniece, let me read a story she was in the process of writing. It was about a group of owls, and about how the smallest owl decided to leave. I was hooked until I came to the part about the little owl flying away in the middle of a bright sunshiny day.

“Clio,” I said, “this is a great story, but owls don’t like to be out in the daytime. Why did the little owl leave at high noon?”

“I don’t need a reason,” she replied. “It’s fiction, and I can write anything I want.”

And she is absolutely correct. Everyone knows that fiction isn’t true.

However, if you want to write fiction that keeps your readers turning pages, you must convince them that perhaps it could be true. Or, at the very least, convince them to suspend their disbelief for the duration of the story. This won’t happen if they spot glaring errors in your work. How can you get them to believe in your story about owls if you have them flying around during the day without a reason? If your owls don’t behave the way your readers know owls are supposed to behave they will quickly lose interest. And even worse, they will lose confidence in you as a writer. If they do, by some chance, continue to read, they will be suspicious of everything you tell them.

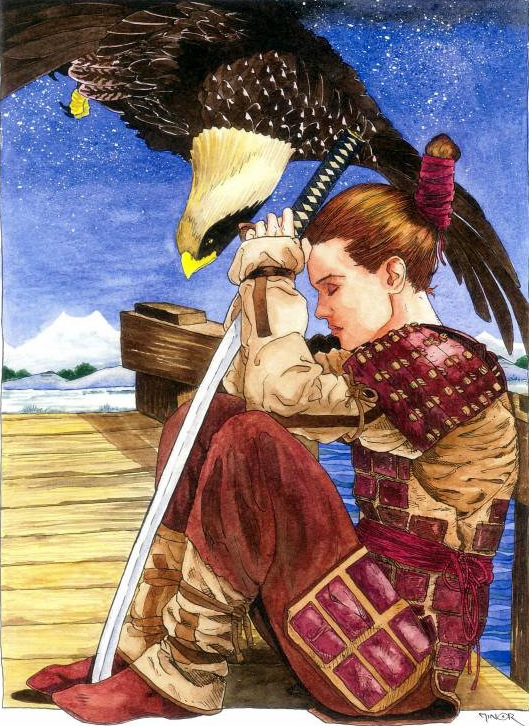

Several years ago, when I was writing the first draft of Forging the Blade, I realized that I needed to learn something about making swords. Duh! In Chapter XIV, which is about the major arcana card, Temperance, a goddess (who bears a remarkable resemblance to Brigid) forges a magic sword for Molly, the main character. She uses Molly’s blood to bind her to the blade. As the sword is forged, Molly is also forged into a warrior. I figured that forging a blade would be a perfect metaphor for Temperance. This is a key chapter in the book, and to make it work, the reader must totally believe in the drama of a piece of steel and a teenage girl being forged into sentient, magical weapons.

The Internet couldn’t give me the information I needed to write a believable chapter. It is an amazing tool for gathering bits and pieces and finding out where to get more, but it couldn’t tell me what a forge smells like, or how a furnace sounds, or how it feels to hammer a piece of steel into shape.

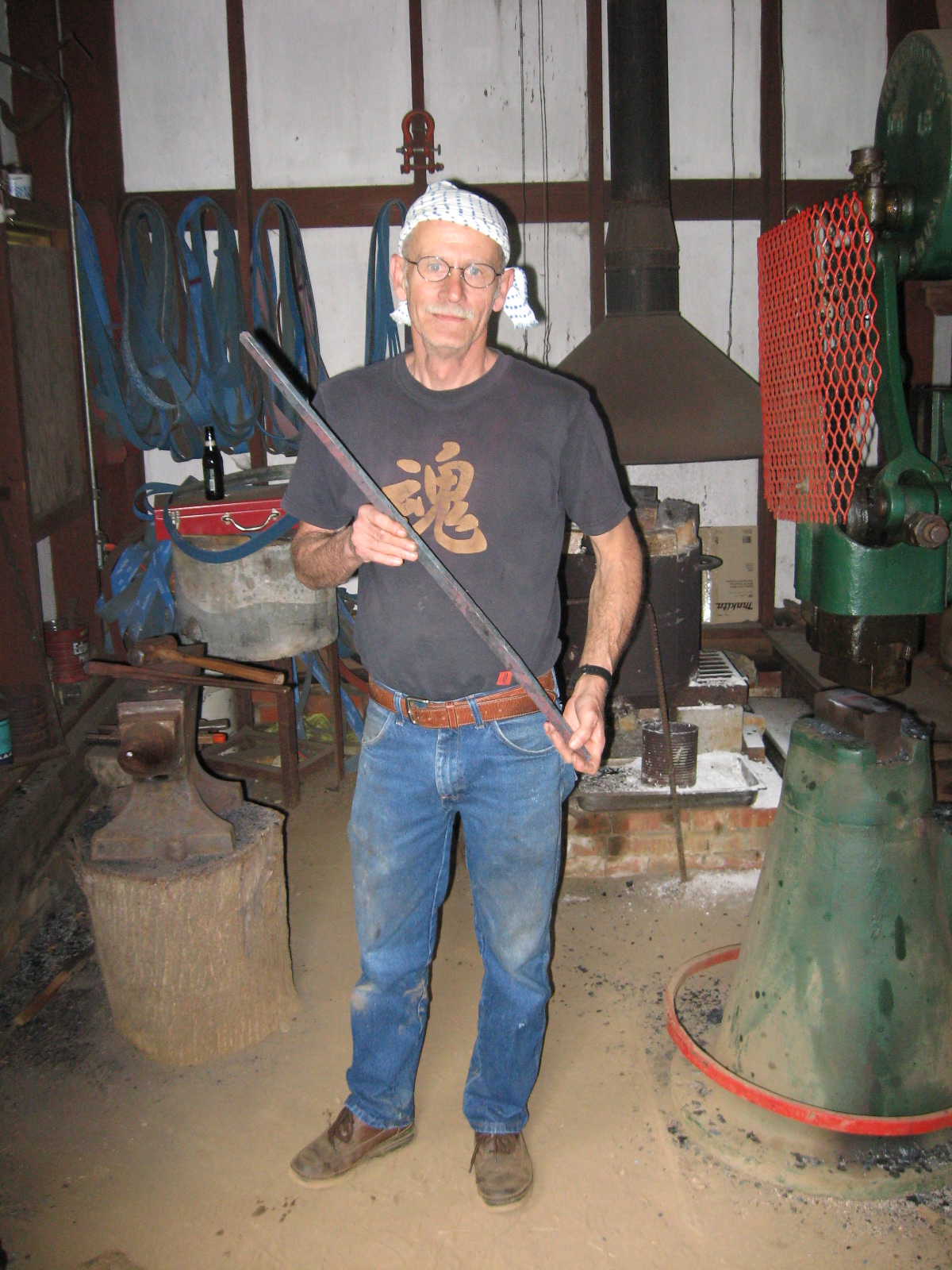

And so, in June of 2007 I drove down the Oregon Coast Highway to Coquille, Oregon, home of Michael Bell, master swordsmith of Dragonfly Forge. He had agreed to let me watch him forge a katana, which is a Japanese sword and exactly the kind of weapon I wanted Molly to have.

The Bell family home and Dragonfly Forge are tucked up in the hills between Bandon and Coquille, Oregon. My first morning there I sat at their kitchen table, drinking tea in front of a wood-burning stove and listening while Michael described the difference between iron and steel and the changes a blade goes through during its forging—in other words, a crash course on metallurgy. Michael is a slender, soft-spoken man, not at all what you think of when you think of a blacksmith. He was also very patient with all my questions.*

After he was satisfied that I had the basics down, we headed out to the small wooden outbuilding which is Dragonfly Forge. There was nothing fancy about it—dirt floors and well-used, simple equipment—but it exuded a comfortable symmetry. Every tool had its place, and I quickly learned that as soon as you were finished using it, it went back in that place.

Michael admits with no shame whatsoever that he cheats. Traditional swordsmiths use charcoal-fired furnaces and they do the rough shaping of the blade with hammers that are nearly as heavy as sledge hammers. His furnace is gas fired and he uses a trip hammer. He also uses electric grinding wheels.

Instead of folding and refolding the billet of steel before he starts shaping the blade, Michael starts with about a foot of steel cable. The cable is perfect, he says, because it’s made from the highest quality steel available; and, since it’s made of dozens of steel wires twisted into a spiral, he doesn’t have to do all the folding. I like the idea of using cable because the spiral is a potent symbol of life and living. As he shapes the length of cable into the sunobe, or rough sword shape, with the trip hammer the spirals of steel wire are forge welded together. If every weld is not perfect, the sword will be flawed and will probably break at the final quenching. It took him until late afternoon to finish the sunobe.

The next day Michael did more shaping. First he cut and hammered out the point. Then he hammered in the three planes of the blade,

The third day was for grinding and fine shaping. When he was satisfied that the blade was perfect, Michael applied the clay in a very specific pattern and let it dry thoroughly. When the sword is heated to yellow hot and quenched in water the clay slows down the cooling. The thicker the clay layer, the slower the cooling. The steel that cools slowly doesn’t develop the large martensite crystals that make the blade brittle enough to hold an edge. It is still strong, but more flexible. The lines of clay that are perpendicular to the cutting edge make stripes of softer steel that act like the discs between our vertebrae. This last step is what allows a katana to hold a strong, razor sharp edge, yet be flexible enough to withstand the strikes of another blade and the forces of cutting through armor, rifle barrels, and torsos.

The final day was for drama. The quenching of a Japanese blade does three things:

It finds the flaws. If the forge welding isn’t perfect or if the architecture of the blade isn’t quite right the temperature extremes will cause the blade to shatter or crack or warp.

It transforms the plain, brittle steel of the blade into a miracle blend of steels so strong and flexible that it can cut through iron or nearly anything else you throw at it.

It accentuates the sweet arc that makes Japanese swords look like they’re ready to float out of your hands.

It ensouls the blade and it becomes some sort of living entity. Really. Ask any Japanese swordsmith.

Michael’s son, who is also a swordsmith, came out to watch. We fired up the furnace, which soon began to roar in an earnest, breathy sort of way. When it was up to heat we closed the shutters on the forge windows and Michael began to pass the blade rhythmically through the hottest part of the flames, heating it evenly throughout its entire length. The darkened forge reached sauna temperatures as we watched, mesmerized, as the blade glowed cherry red, then orange, then yellow. When he was satisfied with the color, Michael pulled his creation from the flames and thrust it into a trough of cold river-water, which hissed explosively. The forge went silent, and we stood in awe as the master swordsmith lifted a perfect blade from the water and another being joined us in the forge. The katana had survived its ordeal of fire, brutal blows, and water, becoming strong and beautiful and alive.

This was an even better analogy to the Temperance key than I had imagined. As far as I’m concerned, truth wins out over fiction every time. As storytellers, we should use it whenever possible. The rest of the time we can only strive for a good imitation.

*Any errors or omissions are mine alone. Michael Bell, of course, knows exactly how to forge a katana.

11 thoughts on “Truth or Fiction? or Yes, I’m Still Working with Temperance.”

I *LOVED* this description of Temperance and the story of the blade. Great chapter!

Thanks Ron, this was a fun one for me to write. The Devil is next!!!!

This appears to be a theme tonight. I also just read something by Neil Gaiman about Jonathan Carroll and the writers/artists he thinks of as the “special” ones:

“It wasn’t those writers or artists who accurately recorded life: the special ones were the ones who drew it or wrote it so personally that, in some sense it seemed as if they were creating life, or creating the world and bringing it back to you. And once you’d seen it through their eyes you could never un-see it, not ever again.” Maybe someday Clio will create a world in which owls fly in the sunshine. 🙂

Thanks for the wonderful description of the forging. I can’t wait to read all the Molly stories someday.

love,

Suebee

Yes, this is the wonderful thing about fiction.

It tweaks reality and makes you see it fresh and new and inside-out.

But first you have to have a good idea about the general consensus on reality before you can tweak it.

I have not doubt whatsoever that if Clio puts her mind to it owls will find a way to fly in the sunshine.

Nice story, Chrissy! Your descriptions and accompanying photos were great. Good job!

Hugs,

Priscilla

Thank you.

Glad you liked it!

Nice story, Chrissy! Your descriptions and accompanying photos were great. Good job!

Hugs,

Priscilla

Thank you.

Glad you liked it!