I found the following comment on my “Virgin Mary, Isis, The High Priestess, and the Empress” blog: “I’ve never really liked the Greek myths….(and I’ve)……always loved Egyptain paganism, because the women have much better and stronger roles, and their gods just seemed more like more ethical, more pleasant people.”

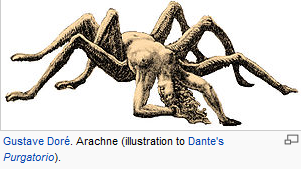

Fond as I am of Greek mythology, I had to agree with him. Zeus and most of the other male gods are obsessed with fighting and sex and spend way too much of their time raping women. Artemis is a spiteful man hater (with good reason, it seems); and Hera, Zeus’s wife, is often portrayed as a jealous, nagging spouse (with good reason, it seems). Apollo and Hermes have the same father, Zeus, but different mothers. They are constantly fighting. Even Athena, goddess of wisdom and weaving, gets so pissed at Arachne, a mortal weaver who claims to be more talented than her, that she turns the woman into a spider. The Greek gods detested hubris, the thought by a mere mortal that they might be comparable to the gods. By contrast, Egyptian gods and goddesses behave pretty much the way one would expect gods and goddesses to act. They aren’t perfect. Set is jealous of his brother, Osiris, and chops him up into 14 pieces and Isis can be tricky, but compared to the Greek gods, the gods of Egypt are, for the most part, “ethical” and “pleasant”.

By contrast, Egyptian gods and goddesses behave pretty much the way one would expect gods and goddesses to act. They aren’t perfect. Set is jealous of his brother, Osiris, and chops him up into 14 pieces and Isis can be tricky, but compared to the Greek gods, the gods of Egypt are, for the most part, “ethical” and “pleasant”.

Why are the two pantheons so different?

Because the cultures that created them were different. Someone (not me) could write a book about how different these two cultures were and why they created such hugely different theologies and pantheons. But this is a blog. I’m just going to tell you what I think, give a smattering of information to back it up (with sources, of course), and then step back and let you tell me what you think.

It is important to remember that classical Greece was not one country. It consisted of a bunch of city-states (Athens, Sparta, Thebes, etc.) that were constantly at war with one another and claiming new territory. Cultures that are constantly expanding and at war tend to be male dominated and value things like beauty, harmony, logic, physical fitness, purity, and strength above all else. These are the same bright ideals that America values, and, like the Greeks, we tend to undervalue the feminine or yin qualities of instinct, feelings, flexibility, circular logic, darkness, and receptivity.

new territory. Cultures that are constantly expanding and at war tend to be male dominated and value things like beauty, harmony, logic, physical fitness, purity, and strength above all else. These are the same bright ideals that America values, and, like the Greeks, we tend to undervalue the feminine or yin qualities of instinct, feelings, flexibility, circular logic, darkness, and receptivity.

Greek mythology reads like a soap opera because it was created by the same sort of very brilliant, very rational, very talented, and very dysfunctional society that created soap operas. (That would be us) And, like soap operas, the main purpose of this mythology was not theological edification it was more about story telling. The Greek myths started out as theology, but as Greek civilization matured and evolved I suspect that the myths were rewoven and retold to suit the changing culture. They began to fall more into the province of art and philosophy.

In her book, Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion, Jane Ellen Harrison does a mind-dazzling job of showing beyond a shadow of a doubt that the classical Greeks practiced two different and separate types of rites.

The newer Olympian rites were the joyous rituals of a favored people who were confident of the beneficent quality of their gods. They included ritual sacrifice of some sort of animal, making a burnt offering of part of it, pouring libations, feasting, and the creation of things of beauty like statues, plays, and poetry, all in honor of the Gods. For the most part, these were masculine pursuits, and most of the people that created the art, wrote the plays and poetry, and formulated the philosophies were men. There is never any mention of sin, atonement, death, or rebirth in the Olympian rites.

The older rites were chthonic (underworld) rituals of riddance, cleansing, avoidance, and aversion. The entities in these rituals were forces of nature, snakes, spirits, and the ghosts of friends, family, and fallen heroes and were considered evil and/or dangerous. The Greeks didn’t worship them; they banished them. The nature of these rites was feminine. Of course, the only description we have of them is from men who were probably never involved in them in the first place.

Isocrates (436–338 BC), an influential Greek orator, had this to say about Greek religion: “Those of the gods who are the source to us of good things have the title of Olympians, those whose department is that of calamities and punishments have harsher titles; to the first class both private persons and states erect altars and temples, the second is not worshipped either with prayers or burnt sacrifices, but in their case we perform ceremonies of riddance.”

The Eleusinian Mysteries seem to be an exception. They were chthonic rituals of initiation of the cult of Demeter and Persephone (Demeter was a chthonic deity).

They were performed underground and were so wrapped in secrecy that we know very little about them except that they had to do with death and rebirth, and that the people who attended them no longer feared death. They were performed for over 1500 years and many famous Greeks and Romans were initiates.

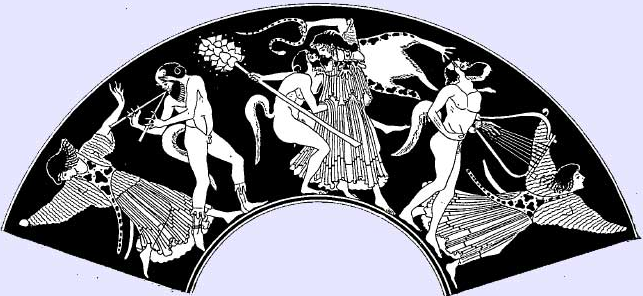

The Greeks didn’t talk much about death. Dionysus, with his myth of death and rebirth, was worshiped in Greece primarily by women, the Maenads. Any man who dared to spy on their wild rites was torn to pieces. (see The Bacchae)

The Orphic Cult was the only other set of Greek rites that I know of that dealt with death and rebirth. Most Greeks believed that when you died you went to the underworld, the chthonic realm of Hades, he who must not be named. By most accounts this wasn’t a pleasant place. When Odysseus visited Achilles in the underworld, Achilles said, “I’d rather be a slave on earth for another man–/some dirt-poor tenant farmer who scrapes to keep alive–/than rule down here over all the breathless dead.” Odyssey, Book II

So it should come as no surprise that in ancient Greece, women were essentially slaves in their own homes. There were exceptions. Spartan women were a bit more liberated. But their babies were still killed if the Gerousia (all male council) decided they were unfit, and their boys were taken from them and raised in military camps. (Wikipedia, Sparta)

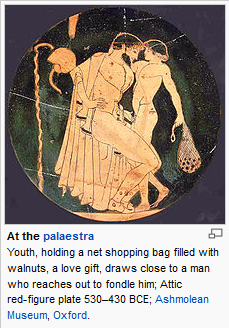

Greek men, apparently, merely lusted after women. Most of the touching, romantic poems were written by men about prepubescent boys. It was customary for boys, especially in Athens, to submit to an older man, who carried them off and became their mentor and lover. (Wikipedia, pederasty and The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony, Roberto Calasso)

Greek men, apparently, merely lusted after women. Most of the touching, romantic poems were written by men about prepubescent boys. It was customary for boys, especially in Athens, to submit to an older man, who carried them off and became their mentor and lover. (Wikipedia, pederasty and The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony, Roberto Calasso)

Greek society was dysfunctional because it was out of touch with its feminine side.

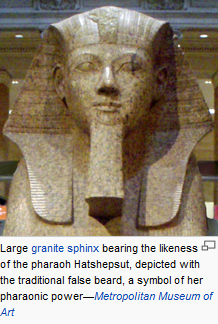

By contrast, Egypt was very much in touch with its feminine side. Egyptian women had greater freedom of choice and more equality under social and civil law than Greek women. There were even women rulers. The most famous was Hatshepsut. Many Egyptologists consider her to be one of the most successful pharaohs. She still had to wear the funny beard though.

and more equality under social and civil law than Greek women. There were even women rulers. The most famous was Hatshepsut. Many Egyptologists consider her to be one of the most successful pharaohs. She still had to wear the funny beard though.

Unlike the Greeks, the Egyptians weren’t into innovation and creativity. Their religion started around 3000 BCE and continued with only minor changes until a century or so CE. There was no layering of one religion over another as we saw in Greece because Egypt prospered for centuries with out being invaded. The Nile River unified the country, and a closely structured, static social system was created to accommodate its life giving floods and ebbs. The religious art is a dramatic example of this conservatism. Egyptian tomb art retains its distinctive, stiff, style over thousands of years. The Egyptians were perfectly capable of creating realistic statues, etc. Some lovely examples have survived. But these creative innovations were not permitted in religious art. They had a system that worked and they were stickin’ to it.

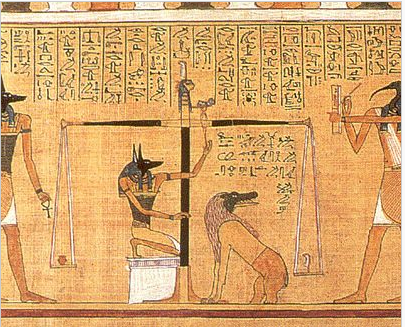

And what was this system? Unlike the Greeks, the Egyptians had a religion that guaranteed them an eternal and blissful life. Not in some musty underworld, but in the bright daylight of the world as they knew it. They could watch over and aid their friends and families and could even speak directly with the gods. It seems that at first only the pharaohs had this privilege, but it eventually was extended to anyone who had led a good, honest life and knew how to navigate the terrifying netherworld known as Duat. He also needed to know how to declare a blameless life when Anubis, the embalmer and guide of the dead weighed his heart against Maat, the feather of justice.

If his heart was light as the feather he could continue his journey through Duat and in the morning emerge into the daylight and enjoy eternal life. If his heart was heavy, it was thrown to the monster Ammit, the devourer of hearts, and the deceased remained in Duat for eternity. Egyptian religion taught you what to do so in this life you could live an eternal, blissful life in communion with the gods. They didn’t mess with perfection. Their religion had no room for innovative art, philosophy, or creativity. It was all about salvation. (Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead, translated by Raymond O. Faulkner, Introduction by James P. Allen)

The Egyptian system was complete. It integrated yin and yang, night and day, our world and the netherworld, death and rebirth. Each had its time and place and value. It supported one of the most stable and balanced civilizations in history. It follows that the mythology of this culture would also be balanced and ethical.

Does this make sense?

6 thoughts on “Why does Greek Mythology Read Like a Soap Opera?”

many points well-taken, but I think the Egyptians, having a long agricultural history, might come off better, and more female-centric from our perspective than the Greeks, who lived in crowded cities with unfertile soil, necessitating the conquest of neighbors to support their population. Both culture complexes contributed mightily to science, philosophy, and the arts, but I can’t get past the thought that both were built on the backs of slaves. But then, what culture hasn’t?

Quite true.

It makes sense that the physical terrain and resources of a region contribute to the theological constructs developed by a culture. A clear point here is that the Egyptian theology reflected a unified/harmonic culture, where as the Greek reflected the compartmentalized struggle bound system of city states.

I do not go so far as to say we create the Gods in our image, yet our self image (our Point Of View) influences how we SEE them. The Greek culture was more us/them struggle focused, where the Egyptians had a common threat (Sahara) and savior (Nile). I think, once you get the Divine Model to be unified, it is easier to unify the mortals that follow that model.

Yes, Exactly.

Re creating Gods in our own image, Emile Durkheim, called the “Father of Sociology” was pretty sure that we did just that. In his “Elementary Forms of the Religious Life” he used anthropological data from non-European societies and compared it to European religious concepts and structures. He argued that, for example, the concept of the “sacred” grew out of a kind of emerging collective unconscious some of which, being unexplainable in naturalistic terms but still being worthy of attention and devotion, evolved into the “sacred”. But, as American Anthropology was to demonstrate a little later, each culture springs from a combination of economic and ideological concepts that gives the culture a unique and idiosyncratic history.

So, a culture that is based on agriculture and the type of communal activity required to maintain it (particularly appropriate for Egyptian society with it’s seasonal cooperative agriculture – a type of collective consciousness that was underscored by the building of pyramids, almost a stereotype of collective activity ) would produce a different religion than a culture based on a kind of internecine perpetual state of competition and internecine warfare. (In Egypt the conflict was mostly at the top of the heap while the culture remained cooperative with rituals of cooperation; in Greece the competition was city state versus city state producing a “masculine” religion with the role of women devalued, a state mirrored in America today where it’s only in very recent times that women have been allowed into combat, for example.

I’d totally forgotten about Emile Durkheim.

Next time I write a blog like this I’m gonna get you to write it for me. 🙂